There can be no doubt that the artistic and architectural heritage of Florence embodies civic pride, and its ability to influence both the ruling classes, including its religious leaders, and the general populace, in the establishment and maintenance of power structures. For centuries, Michelangelo’s sculpture of David has stood as testimony to this pride, reflecting the idealized beauty and inherent strength of man as central to the Florentine ethos. Created at the height of humanism and clearly celebrating the human form as the foundation for harmonious proportions, David’s masculine presence doubles as an indication of an invincible political force. Its physical position outside of the ‘town offices’ reinforces this tradition and demonstrates its importance, both symbolically and politically.

The Medici family, while intermittently holding the reins of power, commissioned works of art for both public and private consumption. In contradistinction to Plato’s expulsion of art as potentially corrupting of the Polis, patronage of monumental works was an indication of position. Enormous power is thus ascribed to these works as vehicles of dominance and this power is reinforced within the domicile as subject matter literally extends the patriarchy into the home.

In Plato’s Republic, the Polis, in order to function as a just society, assigns roles to citizens, allowing all to work for the greater good based on their heritage and abilities. The role of each individual is to perform according to his assigned task, along the virtues deemed worthy. Women were equated with emotional, perhaps even creative states of mind, and thus repressed as less desirable members of this tightly controlled community.

In contrast, art, for the Medici, had the power to perpetuate this male dominant structure as can be traced in Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Woman, wife, or feminine presence is but a possession, existing as progenitor and pleasure center for the men in control. A reading of Titian’s painting, its idealized form notwithstanding, delivers a woman whose life is predetermined by her position and role in relation to the man who has just taken her virtue. This brings the power and dominance of David to the bedroom, and to the nature of the marital relationship of the time. The psychological power of this painting lies in the woman’s expression, the convergence of submission and defiance that is experienced in her inescapable gaze. The clarity of language employed by Titian allows for a comprehensive textual reading which describes servitude, loyalty, lost innocence and perhaps even a degree of pleasure denoted by the deliberate placement of her left hand.

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus was allegedly a gift, commissioned by the Medici and intended again as a private object of art. In it, the viewer can decipher the emerging appreciation for ideal form, inspired by Greco-Roman sculptures being studied at the time. Botticelli’s Venus is idealized and beautiful, reviving a narrative that places these attributes in the center of the philosophical dialog.

Art is indeed a powerful vehicle. It can reflect position, wealth and influence. It can purchase favor with religious leaders and expunge a wealthy being of earthly sins. It seems the Medici, and other patron families of the Renaissance, understood this well. While poetry and art, for Plato, would undermine the authority of the state, it would enable the ruling Florentine families to hold fast to their rank. The enduring nature of this phenomenon continues today as Florentines grapple to keep ownership over this work of art.

* * *

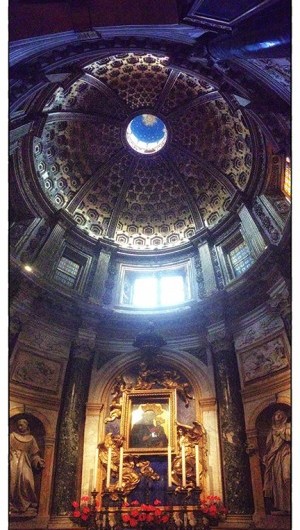

As mentioned above, the contemplation and study of the Greco-Roman statues and texts assisted in ushering Renaissance Humanism as the core philosophical thought. Literally a rebirth of ideas, the layering of the ancient Rome into Florentine art highlights the cyclical nature of time and history, offering a clear picture of how the past is carried forth into the present in a never-ending conversation. Roman ideals of beauty and proportion were adopted in all facets of Florentine life — from the printed word and typographic design, to the construction of architectural monuments. At the root of this movement is the human form—an embodiment of the pinnacle of harmony in space.